The Schedule of an MEP

Parliament Session in the faction room of the European People’s Party in the European Parliament in Strasbourg. Copyright by MEU Strasbourg on Facebook.

It’s Sunday and it’s already two weeks that I’ve been in Strasbourg. The simulation of the EU parliament has been great. I thought initially that I would blog every day of the week, but I resigned from this idea already after my post to day 1 in favour of sleeping at least five and a half hours per night which have been in any case too few.

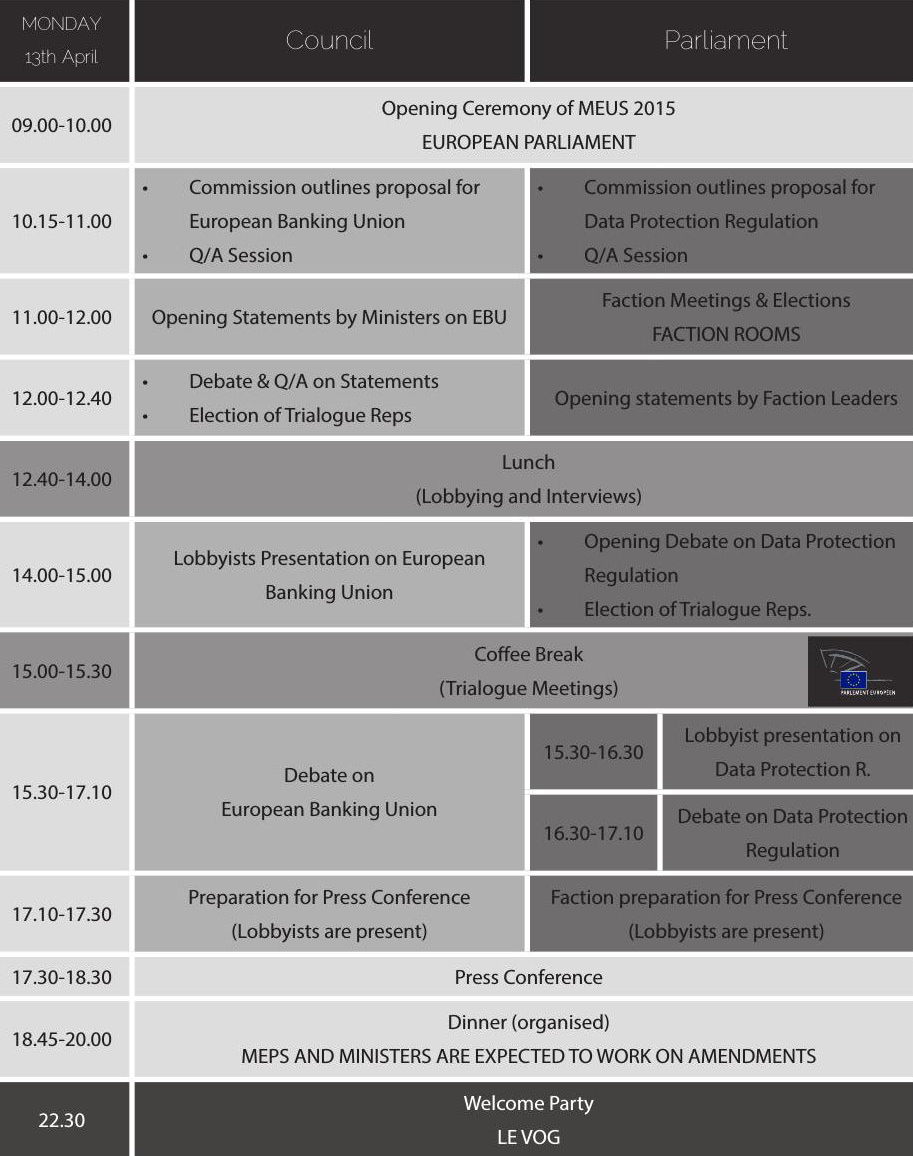

I wont try to reproduce in detail what we have been doing. There has been an enormous schedule of sessions in the parliament and a social program in the evening. Usually, we got up by 6:20 am to pass the security at the European Parliament entrance before 8 am. We left the parliament around 6 pm. So what happened in between?

The simulation comprised moderated, formal debates within the members of the parliament (MEPs), press conferences of the faction leaders and lobbyists, hearings of the commissioners, votings and informal debates in the hemicycle (first picture), faction rooms1 or on the floor during coffee breaks. The sessions of the the council of ministers took place in parallel and we met them mostly “after work”2.

For this post, I will pick some concepts we got to known that you might find interesting.

Formal Debate

Factions have at least 25 members, but can gather much more deputies. The European People’s Party (EPP) faction counts about 270 peoples. While it might be possible for smaller factions to have informal discussions, the EPP need already a better plan to manage their sessions. This is even more true of plenary sessions of the European Parliament in the hemicycle with more than 700 deputies.

The concept they agreed on is referred to as “formal debate” which means that a-priori nobody is allowed to speak. The MEPs can ask to get added to the speakers list (first come, first speak) to have one’s say for a very limited moment of time (30 seconds to two minutes or so). A chair will guide the session and pay attention that the rules of procedures are respected.

MEPs have further possibilities to intervene. There are so called points and motions that can be raised (literally) during the ongoing debate. Some examples:

- point of personal privilege to be raised if something prevents you from following the debate (no translation, urgent physical need, etc.)

-

point of order to be raised if one considers the rules of procedure violated

- right of reply to be raised if the personal or national honour was violated during debate

- blue card (point of question) to be raised to ask a question related to the previous speaker; question doesn’t need to be responded to; both question and response have tough time limits of about 30 seconds

The blue card is naturally the most used mean to engage. After listening to the contribution of a deputy from the other wing, one might have the urgent need to file a blue card to explain that s/he is all wrong. Unfortunately, this is not a question. So one has to formulate these sorrows a bit tactically.

Furthermore, there are so called motions to influence the procedure of the session.

- motion to close the speakers list to ask for a vote to not accept any further speakers added to the speakers list

- motion to reduce/extend the speaker time to ask for a vote to change the speaker time or the time for blue card questions

- motion to suspend the formal debate for x minutes to ask for a vote to make a little break to get up and speak with your fellow MEPs

- motion to open a catch-the-eye debate to ask for a vote to start a less formal debate for certain amount of time

The European Parliament published a page concerning the plenary sessions and there is a more juridical text about the procedures as well (in 20 languages).

Formal debates felt in the beginning somehow artificial. There is no real discussion, because on every contribution, there are only very few blue cards allowed and the next speaker addresses potentially a very different topic. As most of us in the simulation are not trained to use this discussion format, it is difficult to build upon what has been said already and make an own point as well. I spoke few times and found it difficult to explain a complicated topic in only 90 seconds in a way that it is clear to everyone. Don’t forget that everything is interpreted at the same time to many languages. So if someone speaks in Polish, the deputies from Portugal listen to the interpretation from English provided by the Polish interpretation booth. So there is at least a delay and if you mess up your speak, there is hardly no chance that interpreters can get the sense and everyone is lost.

Message Passing System

Imagine you are debating the responsibility of the European Union for the victims of non-developed worker rights in Bangladeshi textile industry (happened this week) with 700 MEPs (admittedly: probably there have been less). You have an urgent question to the beautiful MEP from the Green faction in the other part of the hemicycle.

Where did you buy your clothes? Wanna have lunch with me? / Robert

Of course, you cannot use a blue card for that, because you can only ask questions to speakers. It’s most probably not important enough to raise a point of personal privilege either. So what? There is the awesome message passing system! It’s like in primary school. You write your message on a little sheet of paper and ask your neighbours to pass it around if it’s for someone close to you. Otherwise, there are dedicated note passers that will come to your seat and deliver your message in discretion.

Unfortunately, this is not a very secure system. During the simulation, I received

fraud messages: People writing messages secretly signed on behalf of someone

else. Nice hack. That’s how you seed doubts within your opponent factions. ![]()

Amending Law Proposals

At some point, MEPs will discuss their amendments in the hemicycle. There is a draft of a legislative document (either a direction or a regulation) and MEPs can propose changes to the text. During the session, they will speak up to present their amendment. Other MEPs will speak for and against this proposal and ask questions.

After all amendments have been discussed (formal debate), the MEPs are asked to vote on it. Certain quorums need to be assured therefore. Then, the voting is carried out using small terminals on every seat in the hemicycle. I will write another post on the very interesting issue that voting is.

-

It might be a bit confusing. The real hemicycle offers 751 places and is huge. We have been in there on our last conference day. As our parliament assembled about 80 MEPs, our parliament sessions took place in the actual faction rooms that offer place for at least 200 people. So there was place for all participants including around 28 ministers of the European Council, lobbyists, journalists, commissioners and conference organisers. ↩︎

-

That’s why there have been elected members of the parliament being responsible to communicate with elected ministers during the coffee break

(a.k.a. Trilogue Meetings) to insure that an agreement

can be found later on. ↩︎

(a.k.a. Trilogue Meetings) to insure that an agreement

can be found later on. ↩︎